History

Discovery and Origin

The Game of Ur is one of the oldest known board games in the world, with its earliest examples dating back to

the early third millennium BC in ancient Mesopotamia. The game derives its modern name, The Royal Game of Ur,

from the site where the most intact boards were discovered.

Between 1926 and 1930, English archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley unearthed five lavish game boards during his

excavations of the Royal Cemetery at Ur (in modern-day Iraq). Following this seminal discovery, similar boards

or game sets have been found by archaeologists across a wide geographic range, including sites in Iran, Syria,

Turkey, Sri Lanka, and Cyprus, demonstrating its extensive popularity across the ancient Near East and beyond.

Notably, four boards featuring a similar track layout were also discovered in the tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh

Tutankhamun, highlighting the game's cross-cultural appeal.

Popularity and Fate

The Game of Ur was enjoyed by people from all social classes. It remains uncertain what precisely led to the

gradual demise of the game during late antiquity, around the 7th century AD. One common hypothesis suggests

that the core mechanics of the game survived and developed into backgammon and other similar race games.

The game was designed for two players, evidenced by the discovery of two distinct sets of playing pieces

(typically seven pieces each, often distinguished by color or design) found alongside the boards. For

gameplay, tetrahedral (four-sided) dice were used to determine movement.

The Reconstruction of Rules

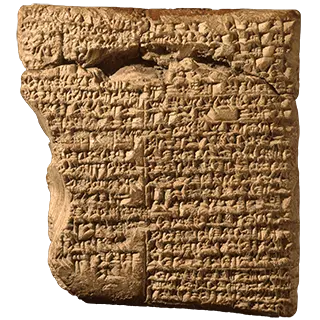

For decades, the original rules of the game remained a mystery. However, in the early 1980s, British Museum

curator and Assyriologist Irving Finkel successfully reconstructed the basic rules. Finkel based his work on a

single, crucial cuneiform tablet discovered in Babylon (modern Iraq) in 1880, now cataloged as (Rm-III.6.b – 33333B) and

housed in the British Museum.

This tablet, dated to 2nd century BC (meaning it describes a late version of the game), contained an almost

complete set of playing instructions, including the number and names of the pawns and detailed information

regarding the dice throws and special squares.

The Ambiguous Path

While Finkel's work clarified the rules of movement and capture, the original route players followed across

the 20 squares of the board is not explicitly depicted on the cuneiform tablet. This missing visual

information has led to multiple scholarly interpretations, demonstrating that the game’s core objective

could be achieved using different paths. As a result of this ambiguity, there have been a few proposals by

different researchers as to which path the

players follow across the board. I will introduce four specific adaptations to the rules: R.C. Bell/I. Finkel,

H.J.R. Murray's, J. Masters, and D. Skiryuk.

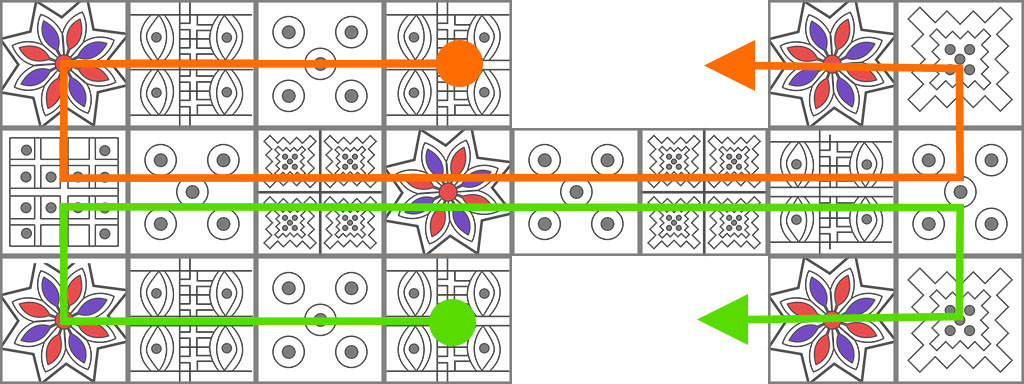

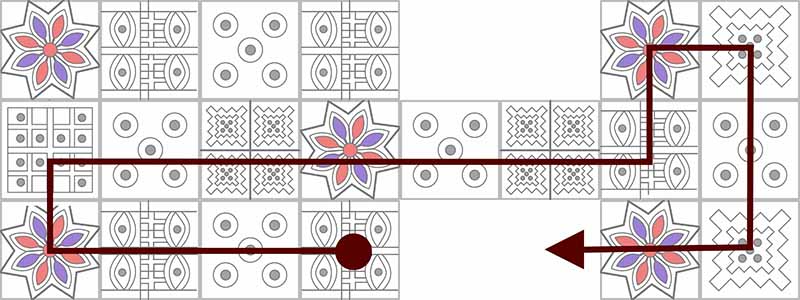

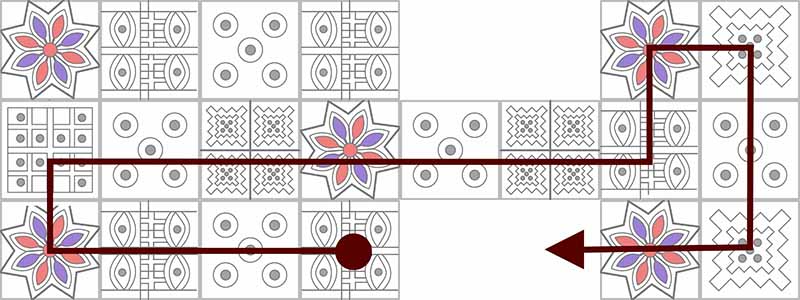

R.C. Bell / I. Finkel

This path is the shortest of these four versions and is perhaps the most widely used direction, fitting

the description of the game found on a clay tablet.

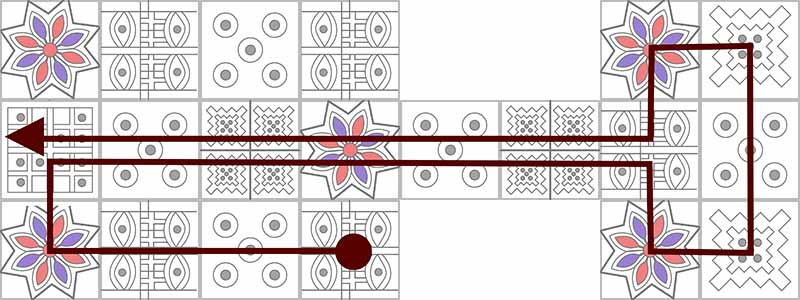

H.J.R. Murray

H.J.R. Murray assumed that the rosette squares gave an extra move. The distance between the rosettes

was equivalent to the maximum points of the dice.

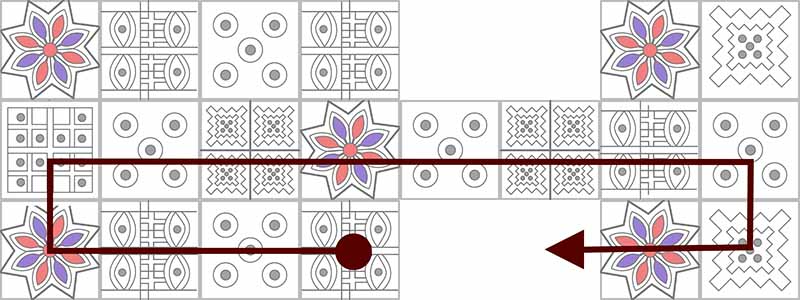

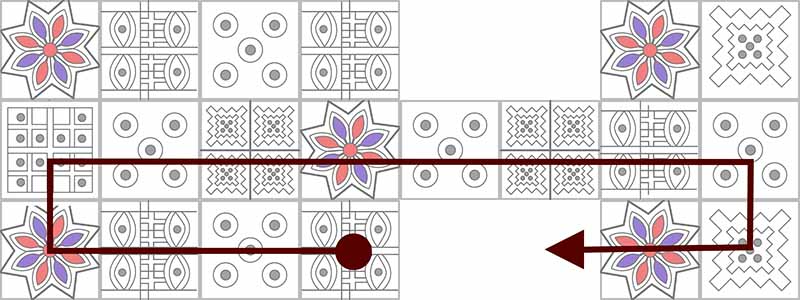

J. Masters

Game board maker, J. Masters, offered a compromise between the rules of Murray and Bell.

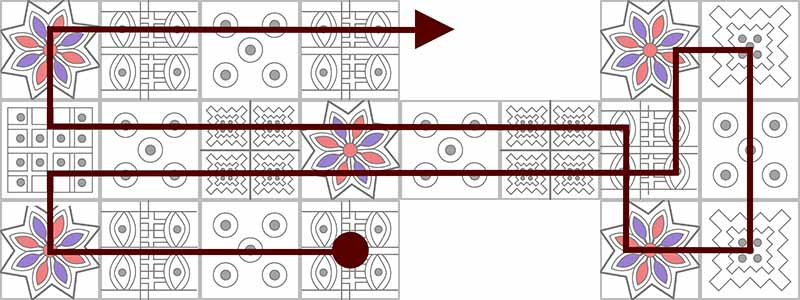

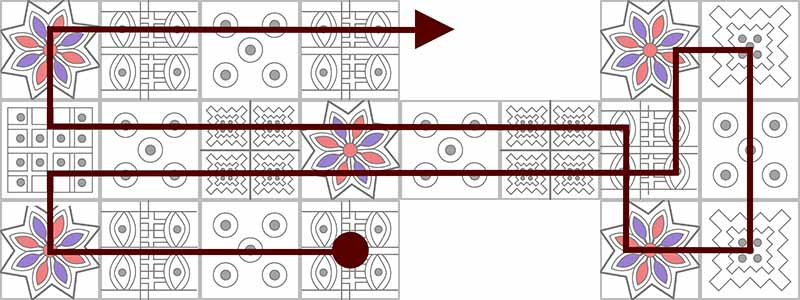

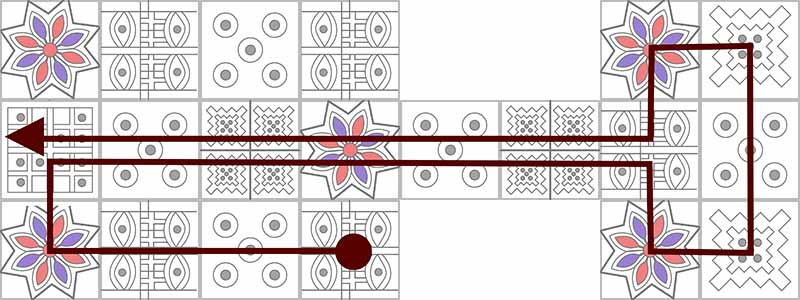

D. Skiryuk

D. Skiryuk presents another alternative with the exit of the board from the middle-left square. It

has a unique ornament on the board. He also believes that some squares had specific functions. The

"4-eyed" square allowed keeping up to four pieces at once, some squares turned pieces upside down, etc.

In unraveling the mysteries of the Royal Game of Ur, we journey through ancient boards and archaeological

clues, discovering a game that transcends time. As the echoes of this ancient past reach

us, we find ourselves immersed in a captivating blend of strategy, chance, and lost traditions. The Royal Game

of Ur, with its enigmatic rules and enduring appeal, stands as a testament to the enduring human fascination

with games that have spanned millennia, leaving an indelible mark on our shared history.

Bibliographical references

- R.C. Bell, Board and Table Games of Many Civilisations, 2 vols. London, 1960, 1969 [reprinted with

corrections and revisions by Dover Books, 1979].

- Irving L. Finkel, “On the rules for the Royal Game of Ur.” In Ancient Board Games in Perspective: Papers

from the 1990 British Museum Colloquium, with Additional Contributions. London: British Museum, 2007, pp.

16-32.

- H.J.R. Murray, A History of Board-games Other Than Chess, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1952, pp.

19-21.